Hank Aaron died today, at the age of 86.

He was a humble and unassuming, a consummate professional – who could hit the bejesus out of a baseball.

Aaron ranks first among all major league players in total bases (6,856, a whopping 722 bases ahead of Stan Musial), runs batted in (2,297), and extra-base hits (1,477), second in home runs (755), third in hits (3,771), and tied for fourth in runs scored (2,174). Somehow, he remains grossly underrated (as does Musial).

Aaron won two batting average titles, three Gold Gloves, and is the only player to appear in 25 All-Star Games. He won only one Most Valuable Player award (1957), but he received at least one MVP vote in 19 consecutive seasons (1955-1973) and finished in the Top 10 in voting 13 times. He endured countless racist death threats before (and for a time after) becoming the game's home run king on April 8, 1974, passing Babe Ruth.

Aaron was routinely brilliant, performing with seemingly effortless grace, but he had little flash, notwithstanding his nickname in the sports pages, Hammerin' Hank. . . .

Aaron did not enjoy the idolatry accorded the Yankees' Mickey Mantle or match the exuberance and electric presence of the Giants' Willie Mays . . . But when he was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1982, his first year of eligibility, Aaron received 97.8 percent of the vote from baseball writers, second at the time only to Ty Cobb, who was inducted in 1936. . . .

Aaron grew up in Alabama amid rigid segregation and its humiliations, and he faced abuse from the stands while playing in the South as a minor leaguer. Years later, he felt that Braves fans were largely indifferent or hostile to him as he chased Ruth's record. And the baseball commissioner at the time, Bowie Kuhn, was not present when he hit his historic 715th home run.

In [1994], Aaron told sports columnist William C. Rhoden:

April 8, 1974, really led up to turning me off on baseball. It really made me see for the first time a clear picture of what this country is about. My kids had to live like they were in prison because of kidnap threats, and I had to live like a pig in a slaughter camp. I had to duck. I had to go out the back door of the ball parks. I had to have a police escort with me all the time. I was getting threatening letters every single day. All of these things have put a bad taste in my mouth, and it won't go away. They carved a piece of my heart away. . . .

At six feet tall and 180 pounds, Aaron was hardly the picture of a slugger, but he had thick, powerful wrists, enabling him to whip the bat out of his right-handed stance with uncommon speed. . . .

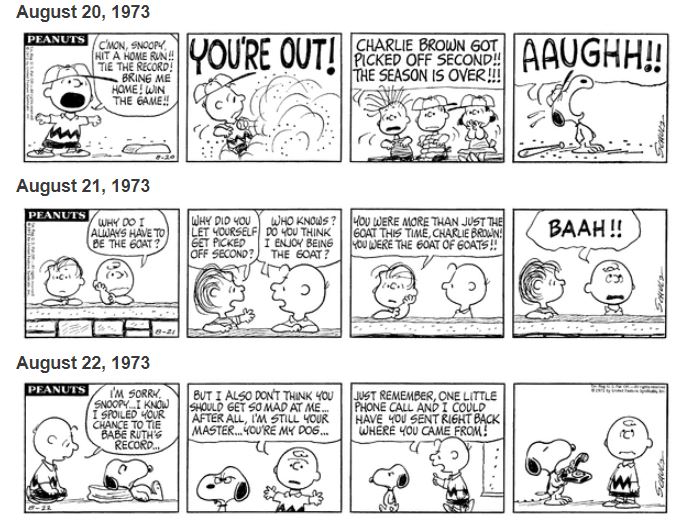

As Aaron chased Ruth’s record in 1973, he finally emerged as a national figure. He appeared on the covers of Time and Newsweek and . . . Charles Schulz, whose "Peanuts" comic strip had become a staple of national popular culture, turned his attention to Aaron in August 1973 with drawings that ridiculed the bigots besieging him*. . . .

[W]hen Aaron hit homer No. 715, Kuhn was not present. The commissioner was in Cleveland, speaking to an Indians booster organization. . . . Aaron viewed it as a snub, and he did not forget it. . . .

Although Aaron wasn't vocal on the larger civil rights scene, he became interested in the writings of James Baldwin, decrying patience in the face of racism. Aaron contributed a chapter to "Baseball Has Done It," Jackie Robinson's 1964 collection of first-person accounts from baseball figures telling of their battles against racism.

"I've read some newspapermen saying I was just a dumb kid from the South with no education and all I knew was to go out there and hit," Aaron wrote. "Baseball has done a lot for me, given me an education in meeting other kinds of people," he continued. But he added pointedly, "It has taught me that regardless of who you are and how much money you make, you are still a Negro."

*: The first Aaron-related strip appeared on August 8, 1973. The storyline ran for two weeks.