Robinson learned his aggressive style of play from the Negro Leagues. . . . Wrong.Robinson's promise to turn the other cheek against the racism he endured on the field lasted many seasons. . . . Wrong.Robinson, a morally-upstanding Christian who did not drink, smoke, swear, or sleep around, was portrayed as a model citizen. . . . Wrong.Robinson's health later in his life suffered because of the abuse he quietly absorbed. . . . Wrong.

MLB continues to whitewash its abhorrent treatment of Robinson in its annual lovefest for #42, presenting and remembering a highly-distorted version of reality. And the sports media has yet to outgrow its blatant double standard when it comes to athletes of colour. To this day, dark-skinned athletes are labelled aggressive and ill-tempered (or just plain angry) while their white counterparts are often referred to as tough, intense, and gritty.

In 1966, Gallup measured his approval rating at 32% positive and 63% negative. That same year, a December Harris poll found that 50% of whites felt King was "hurting the negro cause of civil rights" while only 36% felt he was helping. By the time he died in 1968, three out of four white Americans disapproved of him. In the wake of his assassination, 31% of the country felt that he "brought it on himself".

One does not have to reach back into the historical archives to explain why King was so despised. The sentiments that made him a villain are still prevalent in America today. When he was alive, King was a walking, talking example of everything this country despises about the quest for Black liberation. He railed against police brutality. He reminded the country of its racist past. He scolded the powers that be for income inequality and systemic racism. Not only did he condemn the openly racist opponents of equality, he reminded the legions of whites who were willing to sit idly by while their fellow countrymen were oppressed that they were also oppressors. "He who passively accepts evil is as much involved in it as he who helps to perpetrate it," King said. "He who accepts evil without protesting against it is really cooperating with it."

To be fair, King readily admitted that it was his goal to make white people uncomfortable. . . . [In A Letter from Birmingham Jail, he stated that nonviolent direct action] was an attempt to induce the white community to a point where marginalized people's desperate cries could no longer be ignored.

According to those polls, from 1966 to 1968, support for King among white Americans actually dropped, from 32% to about 25%. King believed most Americans were unconscious racists who refused to seriously examine their racist beliefs, ideas and practices. In 1967, he asked: "Why is equality so assiduously avoided? Why does white America delude itself, and how does it rationalize the evil it retains?" Those questions remain off-limits 55 years later – and will continue to remain taboo for many more years.

King's stinging, blunt rhetoric would have only gotten stronger and more pointed over time. I don't believe King would be well-loved today. If alive, he would be 93 years old. But let's pretend he was 65-70. He might have a majority of support (maybe), but a significant number of Democrats and liberals would be urging King to tone down the anger and take things a little slower.

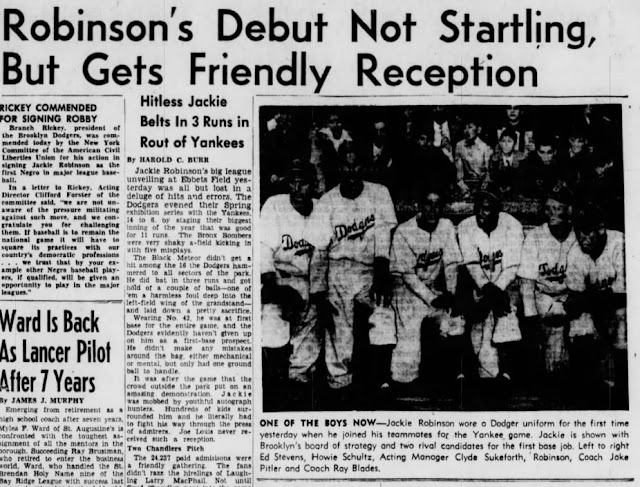

Sportswriters had focused their attention in the run-up to opening day focused on the surprise full-season suspension of the Dodgers feisty manager, Leo "The Lip" Durocher, by baseball commissioner Albert "Happy" Chandler. Along with his close pal, Hollywood star George Raft, Durocher was known to consort with gamblers. . . . Early in 1947, Durocher—who clearly enjoyed the limelight—eloped with actress Laraine Day to Mexico . . . In response, the Brooklyn Catholic Youth Organization vowed to boycott the team's games. . . . [J]ust five days before the season started, Chandler suspended Durocher. . . .On Opening Day, the Brooklyn Eagle, then a large-circulation paper with two daily editions, gave its most sizable front-page headlines to Joe Hatten, the Dodgers' starting pitcher against the Boston Braves. A sub-headline read, "Robinson, Jorgensen in Lineup"—thus equating the first Black player in the modern major leagues with a white fellow rookie memorable only because his nickname was "Spider."

The following day's Eagle coverage was found only in the sports section, although it did include a photo of Robinson shaking hands with Brooklyn Borough President John Cashmore and another with the first baseman in the dugout with his three fellow infielders. . . .Such a reaction stood in contrast to what had happened a few days prior, when the Alabama-born [Dixie] Walker received a chorus of boos during an Ebbets Field exhibition game against the Yankees. Walker was one of a handful of Dodgers players who opposed adding Robinson to their roster. Noting that the jeers came from Robinson fans, the Eagle editorial board denounced the "mistreatment" of Walker, warning that it could imperil the "expansion of the Dodgers experiment in bringing a Negro into the national game." . . .

1947: Dodgers [Robinson's debut], Cleveland, Browns1948: —1949: Giants1950: Boston (NL)1951: White Sox1952: —1953: Athletics, Cubs1954: Pirates, Cardinals, Reds, Senators1955: Yankees1956: — [Robinson retires!]1957: Phillies1958: Tigers1959: Red Sox

the most important person without a doubt in the history of baseball. I would argue that he is the most important person in the history of American sports and he is one of the greatest Americans who's ever lived – period.

Mo Vaughn was on the WEEI broadcast yesterday. Will Fleming (perhaps) asked him if he experienced racism at Fenway, and Vaughn dodged the question, just saying he loved playing for the team. I can't imagine he didn't experience quite a bit of it.

ReplyDelete