In A Game Of Inches: The Stories Behind The Innovations That Shaped Baseball: The Game On The Field, Peter Morris uncovers the first examples (or first known examples) of numerous baseball customs and their developments, most of them (obviously) from the 19th Century. (Morris has written or co-written eight other baseball books.)

The Game On the Field's Table of Contents runs for more than 13 pages and includes 406 subsections. A sampling: catchers signaling to pitchers, home team batting last, choking up, bunts, getting deliberately hit by pitches, swinging multiple bats in the on-deck circle, windups, change of pace, knuckleball, getting batters to chase, keeping a book on hitters, stretches by first basemen, left-handed outfielders, catching from a crouch, infield depth, cutoff and replay plays, basket catches, hidden-ball trick, 3-6-3 double play, delayed double steals, fake to third throw to first pickoffs, pitchouts, hit-and-run, double switches, platooning, intentional walks, don't give him anything to hit on 0-2, first-base coaches, verbal and physical abuse of umpires, appeals on check swings, ball and strike signals, last gloveless player, gloves being left on the field, catchers' masks and shin guards, batting gloves, uniformity of uniforms, and calling time.

Here's one amusing entry (my emphasis):

1.10 Balls and Strikes. As a result of the pitcher's limited role in very early baseball [a "feeder" tossing the ball to the batter, though some pitchers were soon sending the ball in "with exceeding velocity"], batsmen accumulated no balls while strikes were recorded only on a swing and a miss. The premise was that each batter got to strike the ball once and that the pitch was the prelude to the fundamental conflict: the batter's effort to make his way home before the fielders could put him out.

This changed forever when pitchers began to enlarge their role. As noted in the previous entry [1.9 Pitchers Trying to Retire Batters], pitchers were using speedy pitching and spinning their pitches as early as 1856. Other pitchers hit upon the simpler and maddeningly effective approach of deliberately throwing wide pitches to tempt batters to swing at pitches that were difficult to hit squarely. Not only was no skill required for this tactic, but there was also no penalty in the game's rules.

Batters retaliated by playing what was known as the "waiting game" and not swinging at all. This earned them rebukes from journals like the New York Clipper, which wrote in 1861: "Squires was active on the field, but in batting he has a habit of waiting at the bat which is tedious and useless" (New York Clipper, August 14, 1861). Two years later the Clipper added, "The Nassaus did not adopt the 'waiting game' style of play in this match as they did in the Excelsior game. We would suggest to them to repudiate it altogether, leaving such style of play to those clubs who prefer 'playing the points,' as it is called, instead of doing 'the fair and square thing' with their opponents" (New York Clipper, October 31, 1863).

But these were appeals to the gentlemanly spirit, and that spirit was giving way to competitive fervor. While the rules had allowed umpires to call strikes since 1858, few did so, and players were increasingly taking the view that any tactic they could get away with was acceptable.

The result was gridlock. Bob Ferguson recalled in an 1884 interview that "a pitcher had the perogative of sending as many balls as he wanted to across the plate until the batsman made up his mind to strike at one. In an ordinary game, forty, fifty and sixty balls were considered nothing for a pitcher before the batsman got suited" (St. Louis Post-Dispatch, July 10, 1884). Ferguson wasn't exaggerating.

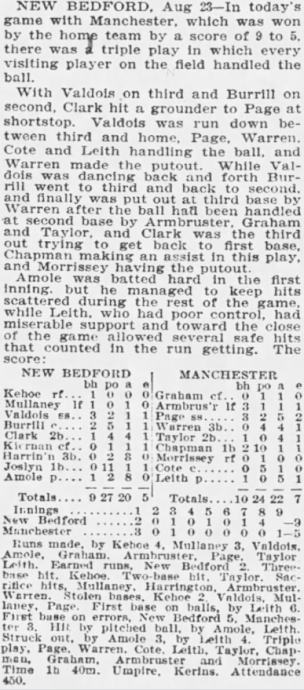

Writing in 1893, Henry Chadwick described the first game of the Atlantics of Brooklyn in 1855: "It will be seen that it took the players over 2 hours to play three innings [2:45], so great was the number of balls the pitcher had to deliver to the bat before the batsman was suited (Sporting Life, October 28, 1893). Baseball historian William J. Ryczek reported that the third game of an 1860 series between the Atlantics and Excelsiors saw Jim Creighton deliver 331 pitches and Mattie O'Brien throw 334 pitches in three innings. Ryczek also cited a tightly contested game on August 3, 1863, in which Atlantics pitcher Al Smith threw 68 pitches to Billy McKeever of the Mutuals in a single at bat (William J. Ryczek, When Johnny Came Sliding Home, 45).

This presented a grave dilemma for the game's rule makers. The pitcher was not supposed to have such a large role, so almost everyone agreed that something must be done to effect "the transfer of the interest of a match from the pitcher to the basemen and outerfielders" (New York Clipper, May 7, 1864). . . . [T]hey attempted to address the problem with a series of tweaks.

In 1864 the concept of called balls and called strikes was added to the rulebook along with a warning system by which the count began only when the umpire decided that either the pitcher or the batter was deliberately stalling. . . .

The umpire thus had a great deal of discretion and, if he believed that the pitcher was trying to pitch fairly, the pitcher could "send a score or more unfair balls over the base before the umpire picked out the three bad ones" (John H. Gruber, "Bases on Balls," Sporting News, January 20, 1916).

This was an imaginative approach, similar to a parent threatening a child with punishment while at the same time explaining that it can be averted if the child just goes back to playing appropriately. Unfortunately this carrot-and-stick approach led only to more creative efforts to grab the carrot while avoiding the stick. . . .

Making the umpire responsible for making such subjective determinations put him in an untenable position. A typical example took place in a July 20, 1868, match in which the Detroit Base Ball Club hosted the Buckeye Club of Cincinnati. When the umpire did not appear, that role was filled by Bob Anderson, a highly respectable citizen who around 1859 had helped found the Detroit Base Ball Club. Steeped in the gentlemanly tradition, Anderson occasionally called balls but never strikes. The visiting players took advantage of this by standing at the plate for up to fifteen minutes before swinging at a pitch. As a result, darkness fell with only seven innings having been played. Most of the crowd had departed long before than.

A match in Rochester, New York, on August 9, 1869, saw the umpire similarly allow a tedious number of pitches to pass without issuing a warning. One spectator became so exasperated that he finally read the rules aloud to the umpire (Rochester Evening Express, August 10, 1869). . . .

It thus became clear that the warning system had failed to accomplish its purpose, and there was a gradual acceptance that the increase in the pitcher's role was permanent. . . .

The rules were modified several times between 1867 and 1875 in hopes of finding a more satisfactory system. In 1875 the rule was again changed ["when nine balls have been called, the striker shall take first base"] . . . Beginning in 1879, each pitch had to be declared a ball or a strike except for a two-strike warning pitch. Since 1881 the umpires has been obliged to call every pitch one way or the other.

The number of balls and strikes allowed changed frequently over the next decade as rule makers sought the ideal balance between hitters and pitchers. Further confusing matters was a peculiar rule that a batter could be thrown out after a base on balls if he walked to first base instead of running. (John H. Gruber, "Bases on Balls," Sporting News, January 20, 1916). (This explains why they were not known as walks until later!)

In 1889, three strikes and four balls were finally settled upon as the parameters for an at bat. And it was not until the early twentieth century that fouls began to count as strikes, a rule change that will be discussed under "Deliberate Fouls," (2.3.2).