The 120th World Series begins tonight in Los Angeles.

It will be the 12th time the Brooklyn/Los Angeles Dodgers and the New York Yankees have met in the fall classic. An average of once per decade. In reality, it's been 43* years since the two teams clashed in October, and half of those meetings occurred in a 10-year mid-20th century span. Yes, from 1947-1956, the Bums and Bombers battled six times -- back in the good old days, when the sport enjoyed a robust competitive balance that no longer exists.

*: RIP Fernando Valenzuela (1960-2024).

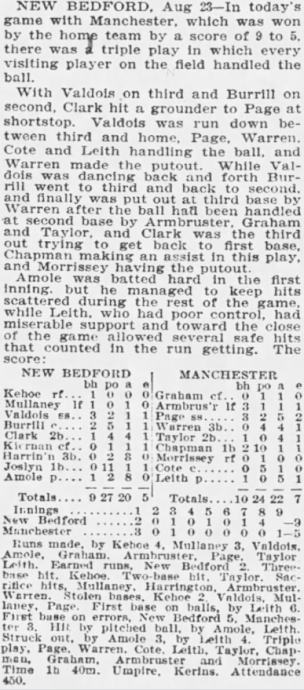

ESPN has a big preview with predictions of how everything will shake out. The pick of who will bring home the Piece of Metal™ was split 7-7:

Yankees in 7 (5 votes)

Dodgers in 7 (4 votes)

Dodgers in 6 (3 votes)

Yankees in 6 (2 votes)

A lot of simulations were run to arrive at these %s:

Dodgers: 52.2%

Dodgers in 4 6.7%

Dodgers in 5 11.8%

Dodgers in 6 16.8%

Dodgers in 7 17.0%

Yankees: 47.8%

Yankees in 4 6.2%

Yankees in 5 13.6%

Yankees in 6 13.8%

Yankees in 7 14.2%

This isn't clickbait. This is engagement bait. This is subscription bait. This is "sign up for auto-renew, then get you hooked on Wordle and NYT Cooking" bait. But it's also a deeper truth that resonates with a lot of baseball fans, and it goes something like this:New York Yankees vs. Los Angeles Dodgers is the most annoying World Series matchup possible. It might be the most annoying World Series matchup ever, which seems hyperbolic until you start looking at previous matchups and realizing most of them didn't have the full force of social media or the Pundit Industrial Complex behind them. . . .Please note that this isn't the same as the worst World Series matchup possible. . . . In the actual 2024 World Series, there will be several future Hall of Famers playing, most of them in their absolute prime, doing unreal things to and with baseballs. It's a very good World Series if you like to watch excellent players and displays of baseball ability. I'm actually excited to watch the baseball part of it, and you should be too.That doesn't mean it won't be annoying, though. Let us count the ways. Haters, gather around. We have some hating to do. . . .

Every October, I warm my heart by thinking about Fox executives who lie awake at night, worrying about a Cleveland Guardians and Milwaukee Brewers World Series. These chuzzlewits and pecksniffs aren't thinking about the excitement a pennant would bring to the areas that haven't enjoyed enough of them (or any of them at all). They're not thinking about specific matchups and baseball-related quirks. They're thinking about eyeballs and star power. . . . This is how they make their money:They make money from eroding your sanity. Their homes are built, brick by brick, from the ashes of your grey matter. They wanted Yankees vs. Dodgers because it would mean they could tell more people that they can have the kind of wi-fi that lets them take ventriloquism classes in their attic, where there was previously a dead spot. . . .Sometimes I'll be falling asleep and think about "His father is the district attorney" out of nowhere. That's a piece of my brain cracking off and floating away, like a calving ice shelf, never to be the same again. Someone has to pay. Preferably, these someones would pay by getting every Guardians vs. Brewers World Series possible.Both of these franchises stare at themselves in the mirror when no one's looking. They also do it when everyone's looking. . . . They insist upon themselves. They think they're better than you and your team. And, sure, by getting to the World Series, that's technically true, but they don't have to insist upon themselves so danged hard all the time. . . .

Yes, the Yankees and Dodgers have more resources than every other team. They spend more money. They're spoiled and so are their fans. They have advantages that other teams don't have with more visibility, cultural cachet, history and purchasing power. . . .But that's letting the other owners off the hook. Mookie Betts is on the Dodgers because Fenway Sports Group Holdings LLC worried about how his salary would affect their abilities to add players to Liverpool and drivers to RFK Racing. They made a business decision, and they absolutely deserve to feel bad about it. . . .

But even though it has the potential to be the best World Series, it's guaranteed to be the most annoying World Series possible. The wrong people have wanted it for years. The team that wins will throw the trophy in an arrogance juicer and get a fresh glass, even though they weren't really running low. The losing team will feel even more entitled at this time next year. And at every moment, before every inning, with every joke and comment on the pre- and post-game show, you will be told just how special this all is.Guardians in six. They have the bullpen, even if the Brewers' lineup is underrated. What a beautiful, simple and boring dream that would have been.

YED 2024 must not go all Great Pumpkin on us.

No.

No.

NO!